greetings, readers & writers,

In class this week, my students experimented with erasure poetry, also known as blackout poetry. We looked at a few highlights in the tradition of erasure poetry—wherein a text might be erased and then reimagined—and how this tradition has often had counter-cultural or activist leanings.

Below, I feature some examples by Solmaz Sharif and Mary Ruefle, as well as some examples in the classroom.

first, try it yourself

I like my students to try it with paper & marker the first time, but it’s also really fun to try out digital tools like this one.

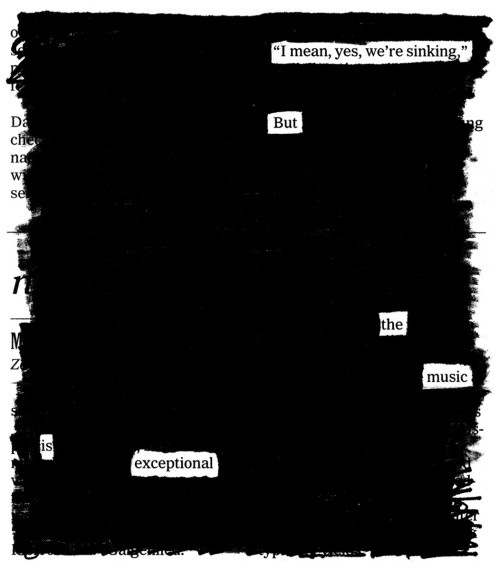

I learned about this handy tool on

’s excellent blog, which includes many of his own wonderful experiments with blackout poetry.My personal favorite of Kleon’s amazing archive is “Overheard on the Titanic”:

Another term for this genre is palimpsest poetry, and there are SO many fascinating examples to look through:

instructions on practicing erasure poetry during the pandemic

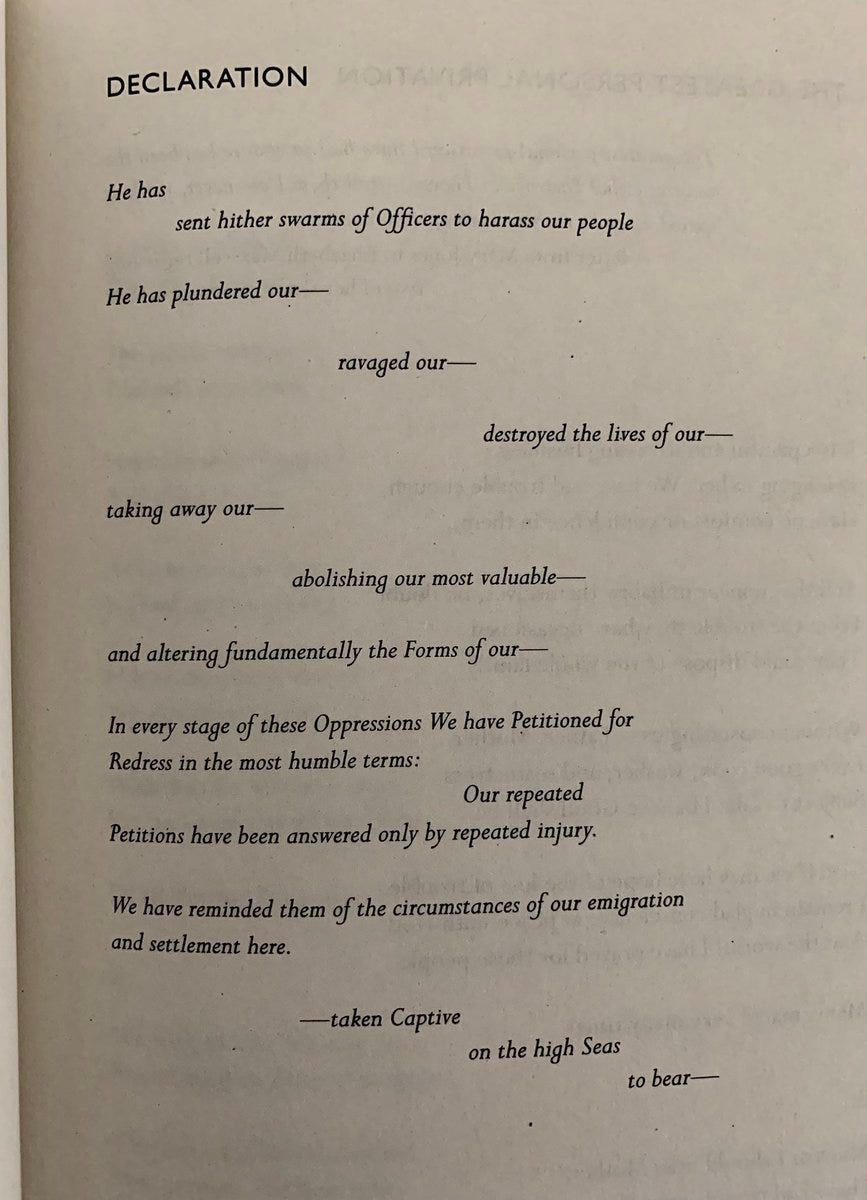

a favorite of my students: former U. S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith uses the Declaration of Independence as the source material for the poem “Declaration”: read and listen here.

Solmaz Sharif on erasure and obliteration

In teaching erasure, particularly in the context of women’s literature, I think of Solmaz Sharif, a contemporary essayist and poet.

Sharif’s work engages with erasure in literal and figurative terms, and I love this short poetic interlude—terse, understated, devastating—which I’ve excerpted from Sharif’s extraordinary essay on erasure:

Erasure means obliteration.

The Latin root of obliteration (ob- against and lit(t)era letter) means the striking out of text.

Poetic erasure means the striking out of text.

Poetic erasure has yet to advance historically.

Historically, the striking out of text is the root of obliterating peoples.

e.g. Hilary Clinton said in her 2008 Presidential campaign: we would be able to totally obliterate them.

The Iranians, she said.

She said, That’s a terrible thing to say but

**

Moazzam Begg is a British citizen who was arrested in Pakistan and detained for three years in Guantánamo. While there, Begg received a heavily-censored letter from his seven-year-old daughter; the only legible line was, “I love you, Dad.”

Upon his release, his daughter told him the censored lines were a poem she had copied for him: “One, two, three, four, five, / Once I caught a fish alive. / Six, seven, eight, nine, ten, / Then I let it go again.”

Source: Poems from Guantánamo: The Detainees Speak (University of Iowa Press, 2007).

Sharif’s use of juxtaposition, cutting with clinical precision from Clinton’s words to the nursery rhymes copied out (laboriously, we imagine) by Begg’s seven-year-old daughter, is abrupt and jarring.

What I find especially powerful about Sharif’s writing is its restraint—the way she’ll quote someone, and then let the words linger in the space that follows, like a dissonant chord left unresolved.

Nothing in a graduate degree in art history prepares you for

the eloquence of the eraser.

-Adam Gopnik

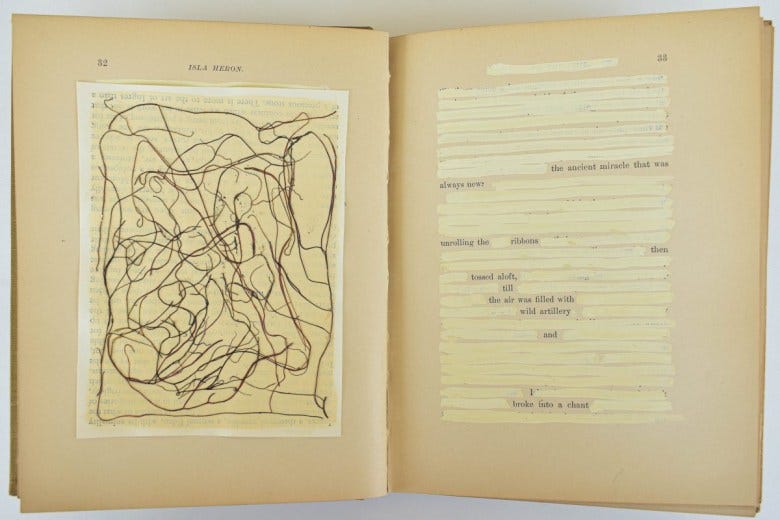

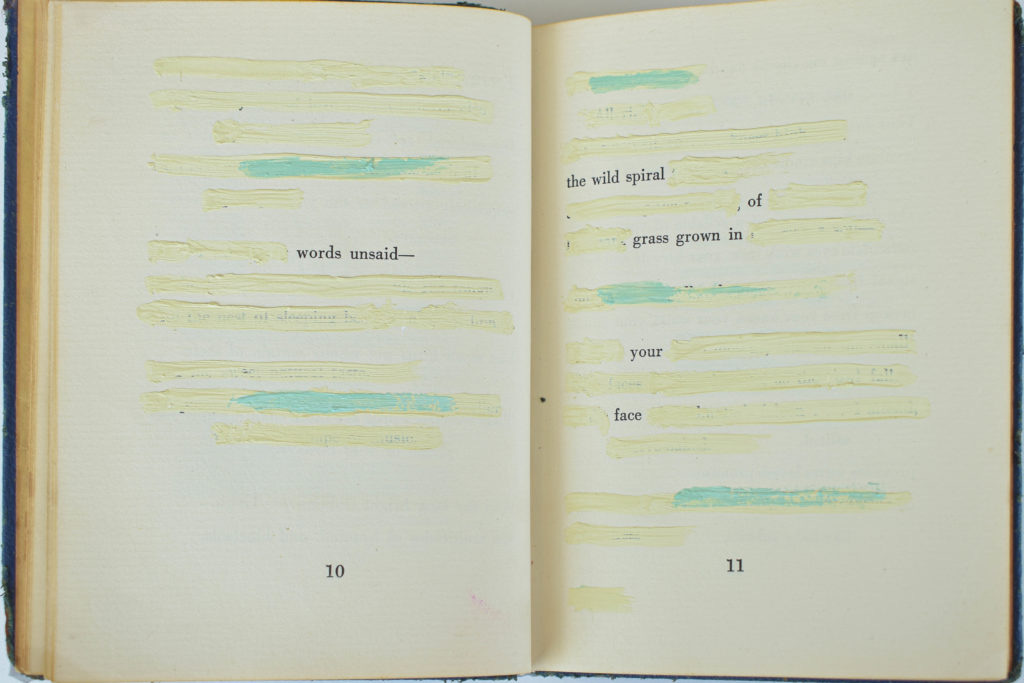

Mary Ruefle’s Erasures

I’m really fond of the writings of poet Mary Ruefle, particularly her elegant work with found texts. She describes the process in terms of discovery and revelation—almost as if the poem takes shape before her eyes:

I describe it like this: the two pages are a field. The words are growing in the field, and they hover above the page. They’re like flowers, and I pick the ones I like. My eye is roaming all over, trying to make connections.

Ruefle’s process is equal parts eclectic and eccentric, resourceful and imaginative:

She uses markers, correctional fluid, paint, tape, and even cuts text from the page with scissors to erase existing words and phrases. Texts, photos, and drawings from other publications make their way into these pages, as well as pressed flowers, handwritten notes, grocery lists, fingerprint samples, tangles of string, and other objects.

Ruefle’s textured, altered pages collectively form a nonlinear but sequential experience-object that playfully questions notions of authorship — whose work is this now? — while bridging, collapsing, and confounding tidy boundaries between image and text, collage and literature.

(Source: Ford)

Maybe, like me, you’re curious to learn more about the matter and material of Ruefle’s creative practice? This interview includes some wonderful gems.

There’s something thrilling and subversive about crossing out a well-loved or authoritative text.

When I teach courses on women’s literature and women’ studies, I love to introduce erasure as a method of reading and responding, and a way to respond to prescriptive texts like etiquette guides or manuals for obedient wives—texts that can (understandably) frustrate twenty-first-century feminist readers.

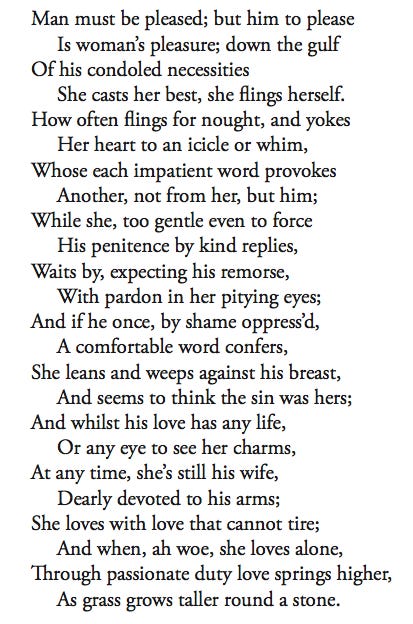

For instance, I sometimes teach my students about the “Angel in the House”: a model of Victorian feminine virtue, wifeliness, obedience, etc. After reading the poem as a group, I ask them to experiment with erasure in such a way as to subvert the original poem’s argument or message.

Take a look at Coventry Patmore’s original poem—a tribute to his wife, Emily, who was apparently a model of feminine virtue— here:

The students have 10-15 minutes to create a blackout poem, and they’re so good! We lay them out on a table, gallery-style, and spend another 10-20 minutes discussing the results.

Inevitably, the students’ smart responses uncover or reveal fascinating patterns in the language—as well as ways to engage with, and often rewrite, that language.

Thanks for reading!

as ever,

EJ

Thanks Emily. I've always loved erasure poems! You might enjoy this piece I wrote about last year: https://sevensenses.substack.com/p/hidden-gems