Today I’m thrilled to explore the life and work of Gabriele Münter, a marvelous German painter and a founding member of der Blaue Reiter, or The Blue Rider, along with Vasily Kandinsky (with whom Münter lived for years, and whose career has eclipsed her own), Paul Klee, Franz Marc, and others.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) offers this overview of the group’s aesthetic priorities:

Formed in 1911 in Munich as an association of painters and an exhibiting society led by Vasily Kandinsky and Franz Marc. Using a visual vocabulary of abstract forms and prismatic colors, Blaue Reiter artists explored the spiritual values of art as a counter to [what they saw as] the corruption and materialism of their age.

The name, meaning “blue rider,” refers to a key motif in Kandinsky’s work: the horse and rider. The group, which published an influential almanac by the same name, dissolved with the onset of World War I.

Read more about der Blaue Reiter here.

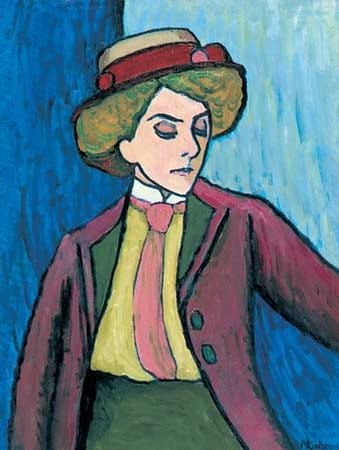

I learned about Münter only recently, and—curiously, surprisingly?—in an extracurricular context. Some backstory: I love to paint, and I take evening courses at the local arts college, usually one course each semester. I’m currently enrolled in a figure painting course, and my wonderful teacher built her entire first session around Münter, specifically this stunning painting.

I was at first a little embarrassed to realize that I didn’t recognize Münter’s name or her work. Based on my cursory reading online, I get the sense that she hasn’t been very well represented in histories of German expressionism. For example, the MoMA resource page I linked above does not include Münter’s name; to be fair, it’s a brief summary—but still!

Similarly, the Wikipedia article about Münter names her as a “founding member” of DBR, whereas the article about DBR barely mentions her. Despite being a founding member, she doesn’t even register in the group’s History section—further evidence that Wikipedia’s gender gap remains very real. (Psst! Join me in changing that here!)

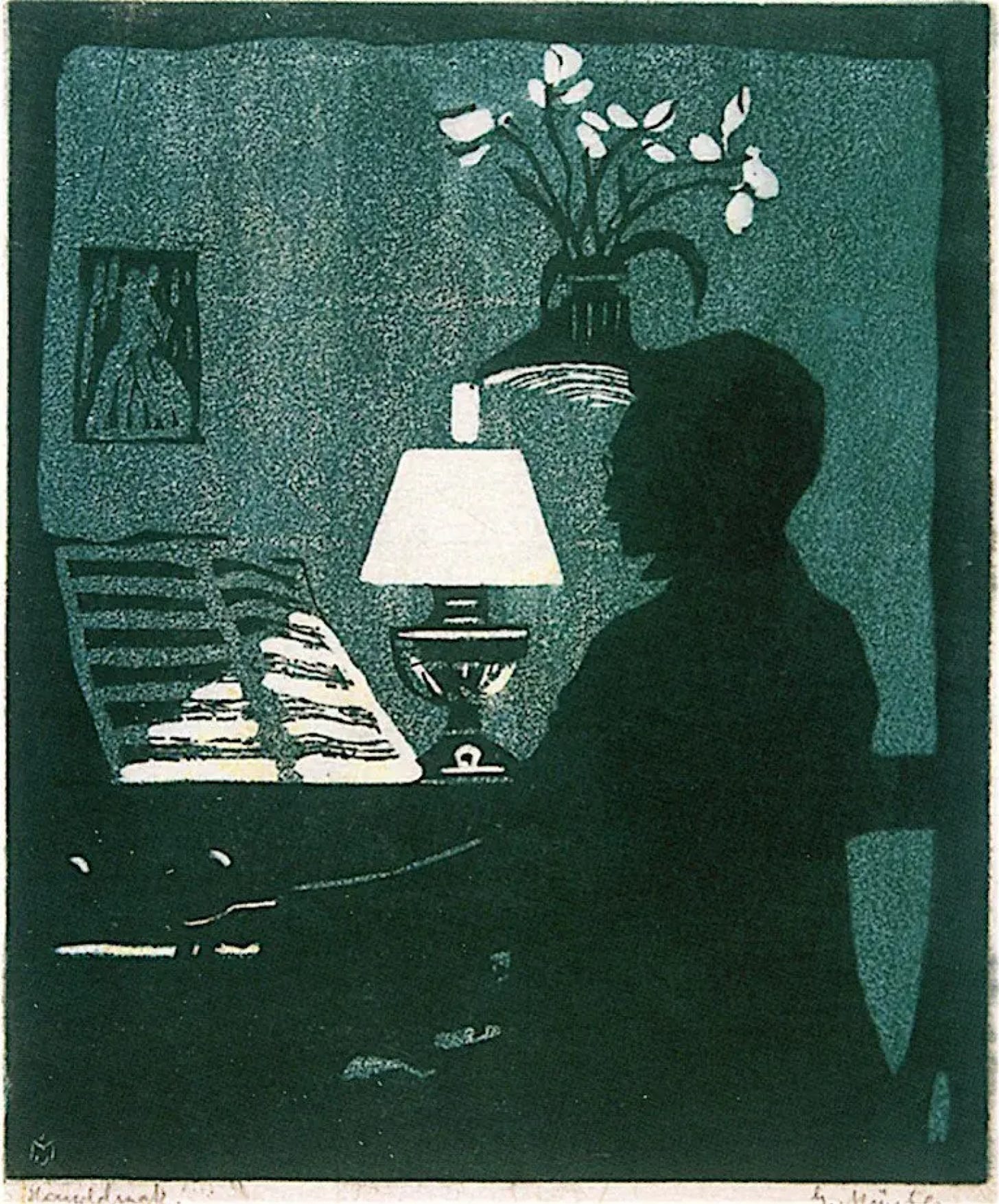

I’m fascinated by the bold, dark, graphic outlines in Münter’s portraits, and her own comments about her background in graphic design, as well as the clear influence her aesthetic had on Kandinsky. I’m in awe of the artist’s precise use of light and shadow in a linocut—and with such restraint and economy, too.

Take a look at this linocut portrait of Kandinsky playing the harmonium:

I read a bit about Münter’s home in Murnau, where she successfully secreted away her life’s work as well as many paintings by Kandinsky and other group members, successfully avoiding Nazi persecution on multiple occasions.

Today, her home is preserved as a small museum. The museum’s website includes some information about the role of place in Münter’s work—as well as the larger project of der Blaue Reiter:

The countryside around Murnau, but especially the house itself, the garden, and the immediate surroundings, were an important source of inspiration for Münter and Kandinsky. They often painted the window views of the church, the castle, or the mountains. It was through his interest in the landscape that Kandinsky’s painting developed toward abstraction.

The Münter House also played a formative role in the history of the Blue Rider. It became an important meeting place of the avant-garde. Franz Marc, who lived in nearby Sindelsdorf, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin, August Macke, and Arnold Schönberg were frequent visitors, as well as collectors and gallerists. Working meetings preparatory to the publication of The Blue Rider Almanach took place here in October 1911. Besides Münter and Kandinsky, Franz and Maria Marc and August and Elisabeth Macke were involved.

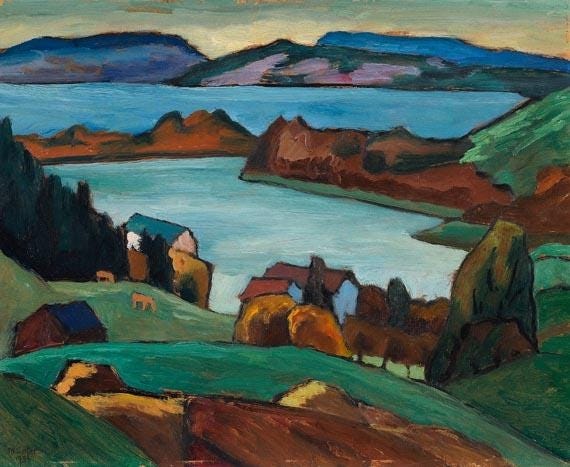

Finally, my first and truest love is landscape, so I found so much to admire in Münter’s 1934 Staffelsee, pictured below, with its rich terra cotta earth tones set against turquoise waters and ominous skies. I plan to copy this painting out myself, probably using gouache rather than oils because the exercise of copying—in the spirit of handmind!— really helps me understand color and composition.

Finally—for some close-up glimpses of those lush colors and painterly brush strokes, take a look at this video about one of Münter’s colleagues (and one of my favorite painters), Franz Marc:

That’s all for today—thanks for reading!

I’m so glad to have learned about Münter! Her paintings are gorgeous. Thank you!